|

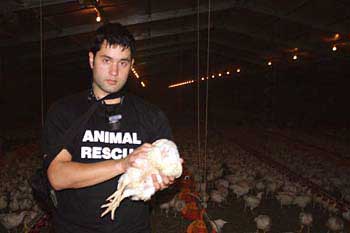

Noah's Ark This profile of ALV Vice President Noah Hannibal is reprinted from the Winter 2004 issue of Voiceworks magazine.

He doesn’t look radical. He looks more like a great big tree you might have whispered secrets to as a kid. Not like someone who had a US secret service agent stand on his head and say ‘If you move I’m going to put my foot right through your head’. Noah Hannibal was three steps away from George Bush before being buried under a mountain of police last year. All he had wanted, Noah claimed, was to ask George’s wife why she was wearing a dead animal around her neck. Dark skinned and quietly spoken, Noah Hannibal is the vice president of Animal Liberation Victoria (ALV), second in charge to Patty Mark, his mother and the founder of the organisation. A world-recognised animal activist, Patty is unlike most mothers, and was pleased to hear the news from a journalist that her son had been arrested in Washington DC in a protest against the wearing of fur. The admiration is mutual. Coming from a part-Chinese background, Noah remembers being five years old and walking to school with his mother, and passing graffiti that read ‘Asians out!’ in large letters. ‘My mum took me right home, grabbed a spray can and took me back and in broad daylight changed it to say “Asians welcome”,’ he recalls.

Did Noah ever eat meat to piss his mum off? Even just once did he stomp his feet and threaten to become a carnivore? Noah laughs, ‘if I was raised in a non-animal rights family I would have come to this point anyway. Might have taken a bit longer, but I would be here.’ That’s not to say Noah didn’t have a tough time growing up. Having bed-hopped a dozen or so high schools, it was finally recommended by counselors that Noah complete his studies by distance education. ‘I’m not one of those people who enjoyed school a whole lot,’ Noah says vaguely. He is now feverishly penning the final chapters of his philosophy PhD on the moral status of animals. Animal Liberation Victoria started when Patty posted up a scribbled note reading ‘Help the Hens’ at the local milk bar in 1978, and has since become an institution with more than 1000 members, and an important role in the global organisation Open Rescue. ‘Open Rescue is about going into places where animals are suffering, exposing the conditions to as many people as possible and getting the animals out,’ says Noah.

The team swarms into factory sheds when farmers have settled down for a spot of evening telly or have turned in for the night, ‘Sometimes you might get scared, but you just remember that it’s nothing in comparison to what these animals are going through,’ said Noah. Wearing bio-suits to ensure they don’t bring in diseases from the outside, and armed with a video camera to leak conditions out to the media, Noah and activists spotlight as many suffering animals as they can and get them out. They often witness battery chicken sheds with approximately 20,000 birds crammed inside, all fed growth hormones and antibiotics to make them lay eggs quickly. ‘There’s always a bunch of birds with their combs ripped off and their brains bulging out from their skulls. They always get euthanised when they’re that bad, but it’s better than slowly dying underneath the other birds.’ ALV films six-week old birds that should be chirping under their mum’s wings but instead are having heart attacks because their internal organs are growing too fast. ‘It’s like putting the weight of an adult human on a newborn baby; their legs just cripple and break underneath,’ said Noah. ‘In these sheds you won’t see a single bird that can walk properly. Most cannot stand and they dehydrate because they can’t get to the water. There are dead birds scattered across the floor.’ Noah describes deformed chickens that fall through the wire floor of the cages into the manure trays underneath and slowly drown in their own shit. Balls of manure harden around the bird’s clawed feet until they flop to their side and spread their red-orange wings out and become splattered in the manure falling like rain. Noah sometimes counts up to 50 chickens stuck in the manure tray at the farms. ‘In one shed there were so many stuck down there that we had to leave the ones we couldn’t reach. It was awful,’ he recalls. Now a puppy mill is a strange phenomenon. While most of us probably thought that puppies in pet shops came from puppyland, Noah and an ALV team took a trip out to a puppy mill just outside Ballarat last month. ‘In this mill they have a holding licence for 378 pups to send out to pet shops, and they’re all crammed in kennels with concrete floors, no blankets and it can get to about zero degrees in winter out that way,’ says Noah. The ALV team filmed the pup’s equivalent of a prison exercise yard that measured two by two metres. ‘The dogs we saw were just miserable. That’s why a lot of the dogs sold in pet shops are quite psychotic, because they’re raised in these pretty appalling conditions.’

Noah doesn’t believe humans are monsters. He just thinks most members of society can’t put two and two together. ‘All it takes is for people to see with their own eyes what happens to these animals and most will give up eating meat on the spot.’ Noah remembers seeing footage taken from inside an abattoir when he was ten. A cow was hitched upside-down on a hook by its hooves and a man stepped up to it and slit its throat. The cow kept struggling while blood poured out of the cut and its head swung back against the floor. It was a far cry from the plastic wrapped cutlets on a tray of Styrofoam he had seen in the supermarket. When I first made contact with Noah he was in China wearing a monkey suit inside a cage outside Columbia University. He and a team of activists were trying to raise awareness of the scientific testing on chimpanzees and baboons openly being practiced on the campus. Which brings us to the ultimate curveball, the question pitched by carnivores aching to trip up animal activists: ‘What if the medical research done on a monkey could save your child, mother or father?’ Noah sighs and calls animal testing in laboratories archaic and predominately unenlightening. ‘We are totally different species with totally different physiologies. Apart from using animals to try to cure human problems that are mostly self-caused, I would think if you were trying to find a cure for a rat disease in a society where humans weren’t morally ‘superior’ you wouldn’t do tests on a human to find a cure for the rat.’ Noah remembers a question first poised by Russian writer Dostoevsky. ‘I’m not going to say it in the right way, but the gist of the question is if you had to kill one innocent child to save million others, would you?’ I wait for Noah to answer himself. ‘I wouldn’t do it. What’s the point of any of us living after doing something like that?’ Noah has seen a grown man who used to slaughter cows break down and cry at a farm animal sanctuary, when a calf who had been rescued from an abattoir came up to him and nestled her head in his chest. That’s the image Noah left with me.

|